July 3, 2022

Text: 2 Kings 5:1-14

A long time ago in a country far, far away, there was an extremely powerful man named Naaman who had a disease with no known cure. (The reference to leprosy, by the way, is confusing. What the Bible called leprosy is not what we call leprosy, or Hansen’s disease, but was probably eczema or psoriasis, conditions which are neither life-threatening nor contagious. But whatever this illness was that Naaman had, we know that it carried with it a deep stigma and was considered incurable.)

So Naaman, a very powerful man, a commander in the king’s army, needs someone or something to do the impossible and cure him. Through the unlikely intervention of a slave girl and a couple of nameless servants, he is offered a simple and direct means of healing. According to the prophet Elisha, all Naaman has to do to be healed is to wash seven times in the Jordan River. And it works.

This story has about it the quality of a fairy tale—the main characters include a scheming king, an angry warrior, a wise sage, and an unexpectedly insightful, caring peasant girl. Furthermore, order is restored when the unlikeliest of actions—much like kissing a frog, or fitting your foot in a glass slipper—is revealed to have miraculous power.

Like many fairy tales, this story has a subversive slant to it, in that it is about the arrogant being brought low, the powerful needed to learn a lesson from those who are beneath him on the social ladder. There’s a twist, though, because it is also about a man who appears to have it all but who is actually in great need and who ultimately receives the gifts of healing, liberation, and faith.

As the story begins, one has the impression that what Naaman wants, more than anything else, is to be cured. What else could he want? Other than his illness, his life is pretty great—he enjoys wealth, power, influence, and the protection of the high king.

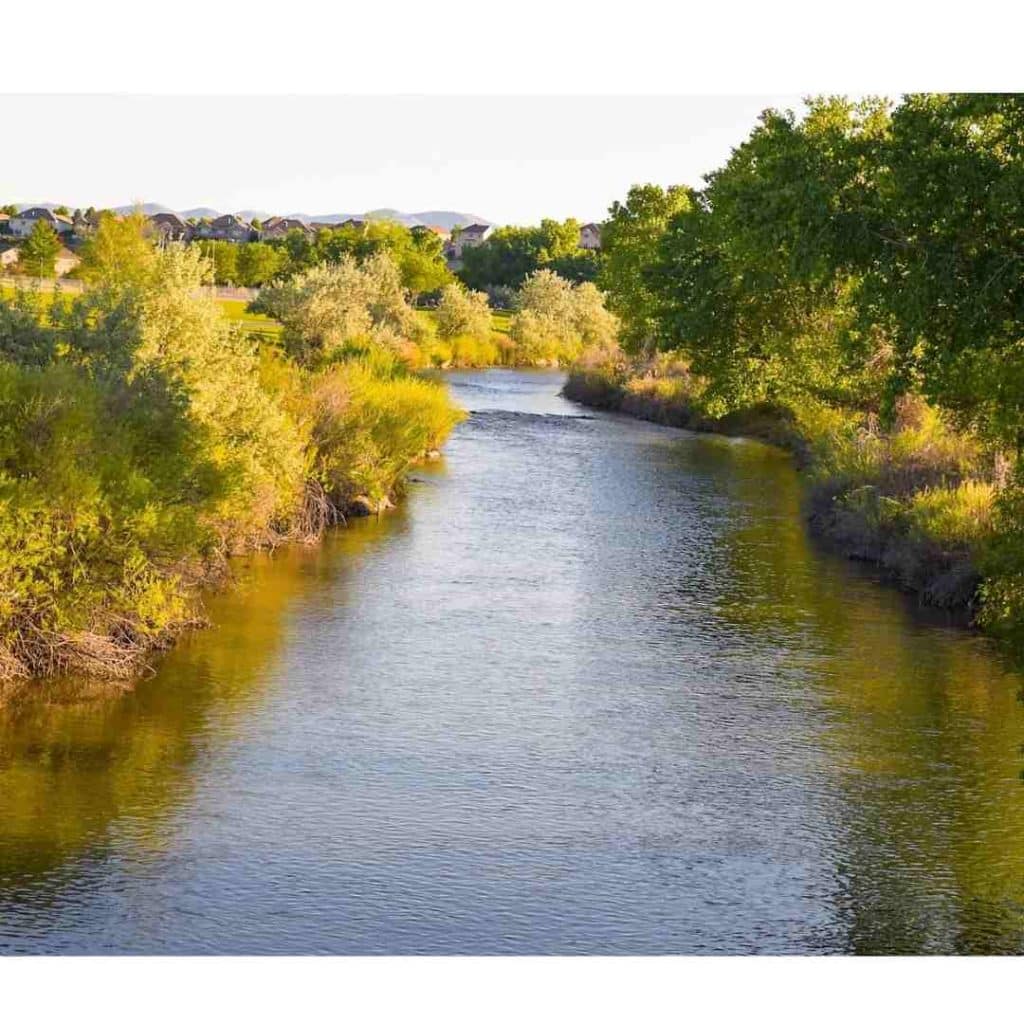

It is when Naaman throws this temper tantrum, mid-story, that we realize that what Naaman wants is not the same thing as what Naaman needs. He wants something more than simply to be made better; he wants the very biggest and best and snazziest cure, a cure that could only be bought at the tremendous expense of ten talents of silver, six thousand shekels of gold, and ten sets of garments, not to mention a letter from the king. He is enraged when what he is offered instead is a free and simple, you might even say humble, means of being healed. The prescription given is utterly beneath him, it is humiliating, or so he thinks, and it isn’t playing by the rules of a transactional society. Who does this so-called prophet, this foreigner, think he is, to tell the great Naaman to go wash in the Jordan River, which is little more than a glorified creek?

Naaman’s wants, his desires, go way past being healed from his physical affliction. And we, the audience of the story, begin to sense that what he needs is also more than a physical cure; what he needs is to be freed from his sense of entitlement, his need to control, as well as from his ego, anger, and fear.

Being washed clean in the Jordan River will of course remind Christians of our baptism. In the context of this story and even of our celebration of Independence Day this weekend, I hope it will also suggest something to us about religious freedom. The one truly free person in this story is Elisha. The prophet has no need of Naaman’s money. He doesn’t care about the political machinations of the two kings. His sole motivation is to use this miracle as a way of demonstrating the power and mercy of God. He wants nothing for himself, which is what makes him so free, while Naaman’s various desires, and indeed his whole way of seeing the world, keep him bound in invisible chains.

Naaman’s story does not end where our lectionary reading today ends. There are two more episodes involving Naaman and his retinue, but I’ll just share the most immediate and relevant one. In the NRSV translation, it goes like this:

“15 Then he [Naaman] returned to the man of God [Elisha], he and all his company; he came and stood before him and said, ‘Now I know that there is no God in all the earth except in Israel; please accept a present from your servant.’ 16 But he said, ‘As the Lord lives, whom I serve, I will accept nothing!’ [Naaman] urged [Elisha] to accept, but he refused.”

Elisha, the prophet, stands firm in his freedom; he needs nothing from kings or warriors. Naaman, the convert, is only beginning to learn what true freedom means. But he is much freer than when the story began, and not only because his skin has been washed clean of disease. He goes to Elisha instead of being angry that Elisha doesn’t come to him; he offers a gift instead of a bribe. He has come out of the muddy waters of the Jordan a new man in more ways than one.

Although this story took place a long time ago in a country far, far away, we live in the same kind of transactional world and are chained to the same myths about power that bound Naaman to an illusion of freedom and security without giving him the real thing. The myth of privilege is that wealth and power and all the trappings of modernity put us above risk, beyond the possibility of being hurt by disease, hunger, and so on. Even though at some level we know better, we cling to the notion that we’re above all that. If we do get sick, we will find someone to fix us. If we’re hungry, the grocery shelves will have food and we’ll have the money to pay for it. If there is a pandemic or the changing climate is driving us toward catastrophe, scientists will find a way out of it. Any scenario that doesn’t fit that narrative is met with fear, anger, or a stubborn clinging to alternative facts.

One danger of this way of thinking is that it becomes a weapon against those without power and privilege. The myth tells us that if only they tried harder, or were smarter, or, basically, were more like the rich white heterosexual male that our society holds up as the norm—if they were just more like that, they would not be in such a pickle. Furthermore, we are all so caught up in this myth that we tend to subconsciously live by it even when we are not part of that white, male, heterosexual norm ourselves. The patriarchy and white supremacy culture are that insidious and that hard to escape.

Our faith offers us a better way, but it is not easy to get there. Or maybe, like washing in the river Jordan, it is deceptively simple to do, as long as we don’t mind risking our whole way of being in the world. When we go down into the waters of baptism, we become disoriented—in a good way. When we go down into the waters of baptism, we come up out of them both washed clean from the old ways of relating to the world and others people, and we find ourselves on absolutely equal footing with everyone else. This will not always feel good, or comfortable, but it will free us.

In an interview I heard recently with Nigerian-born public intellectual Dr. Boya Akomolafe he said, “If people find that they are politically homeless right now, if people find that they have more questions than answers, if they have more concerns than convictions at this moment in time, then I would say that the work has begun.”[i]I would agree. As I see it, that is the work of transformation that is at the heart of our faith—not to be more certain, more secure, more entrenched in our own righteousness, but to be humbler, less attached, and more and more dependent on the grace of God and grace alone.

Naaman’s wealth and influence did not save him. Having command of an entire army did not save him. We must not put our hope in the stock market, or the president, or the Supreme Court. We must seek out a freedom based on something older and more fundamental than our nation’s founding documents. Our baptism makes us citizens of another kingdom. We come to the table to be reminded of where our true dependence lies and where our true freedom is to be found—in community with one another and in communion with God. That is a freedom that nobody can take away. Thanks be to God. Amen.

[i] From the podcast Sounds True: Insights at the Edge